January - August 2020

Designing for Self-Determination:

Making Futures Without Policing

Themes about what design enables and disables from a virtual workshop at the Participatory Design Conference (June 1-16, 2020).

We examined the potential opportunities and dangers of using a design approach within grassroots movements that are building alternative social structures. Workshop participants investigated possibilities and limitations of design as a way of thinking by practicing the practice, in the context of designing for alternatives to policing.

Participants built on community-based precedents to brainstorm and imagine tools and technologies that could replace a call to police in response to a threat. We used this as a collective experience to discuss and debate what design might or might not offer in this context.

Designers claim to be able to shape future ways-of-being by designing artifacts that invite new socio-material interactions. Yet, design is only one way to create the future.

Does design inherently produce static, blueprinted ways-of-being?

Is it possible to design within systems that are relational, cooperative, and

dynamic? How might designing objects help community organizers reckon with the

tools and technologies of existing infrastructures and develop lateral

solutions?

After completing a design exercise online, groups gathered to discuss the results through a facilitated conversation:

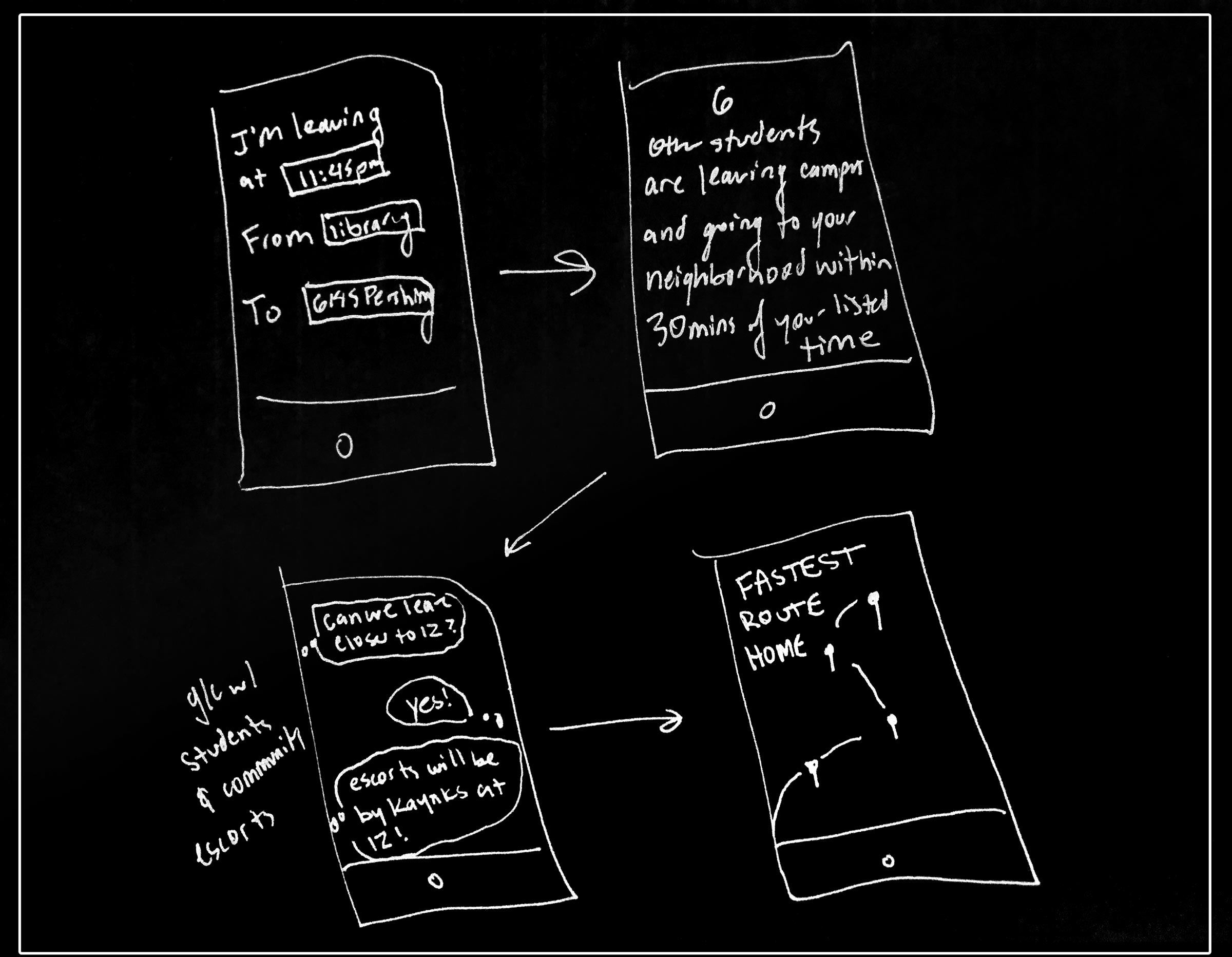

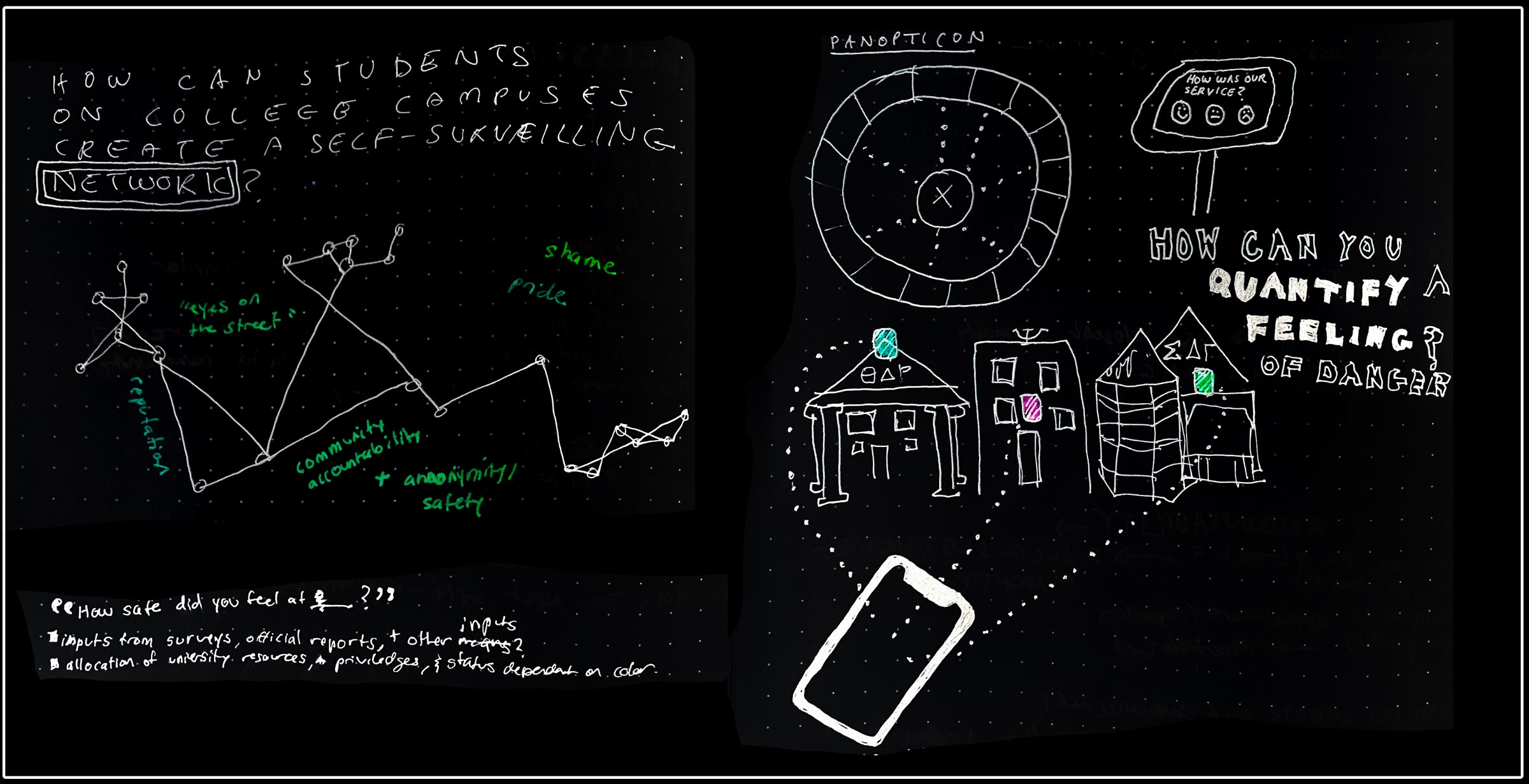

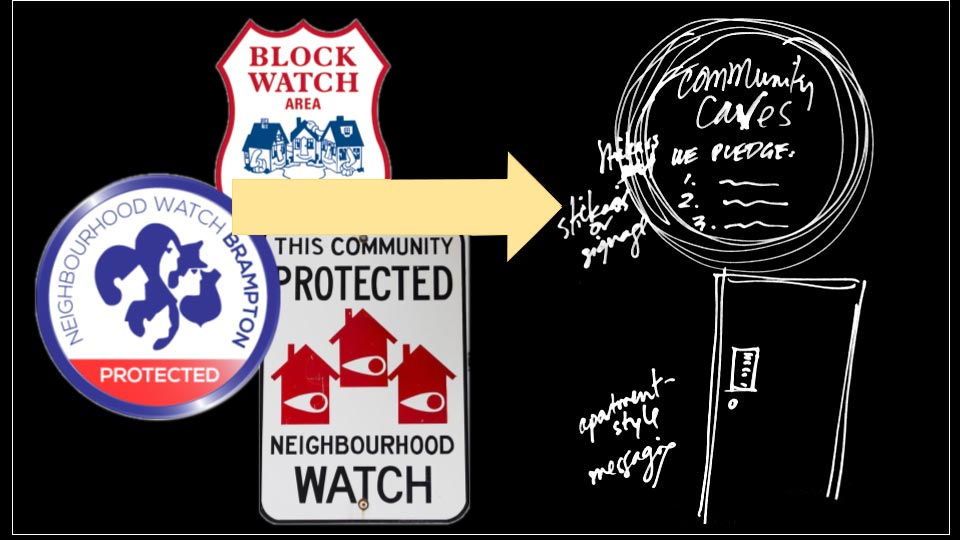

After the workshop, I identified a series of themes that groups discussed. These are shown below, along with images from the design exercise that groups were responding to.

- Who is involved in building alternative social structures like community-led street patrols, community accountability, mutual aid or worker cooperatives? (e.g. activists, community members, elected officials...)

- What was ‘designerly’ about our online design exercise process?

- How would the roles we listed in step 1 go about building alternative social structures in a way that’s different from the process we took on?

- What do we notice about the ideas that were created in our design exercise? What kinds of outputs did we create?

- What kinds of outputs do these other roles create?

- Looking at specific ideas generated through our design exercise, how do they work to achieve the alternative vision they were striving for?

- What designerly practices and ways of thinking are a useful addition to what others are already doing to create alternative social structures, and how are they useful?

- What designerly practices and ways of thinking are likely to interrupt, sideline or challenge what others are doing? How are they harmful?

After the workshop, I identified a series of themes that groups discussed. These are shown below, along with images from the design exercise that groups were responding to.

Dominant Design is about making things tangible.

Sketching and drawing, visualizing our ideas, and mapping/moving around visuals is part of what makes our processes designerly. Designers “think about form and application, or form and function– how will a tool be used, what will it look like?”

This can be useful: visual skills can serve to “make physical spaces welcoming”, to “engage with tangible things and the built environment”, to allow “clear communication” and “storytelling”, to “make resources and knowledge available to others” and reach a broader audience.

Making things tangible can also “help solidify an idea that may be general”. It can help to “show” abstract systems, and to “show prototypes to participants for feedback and editing”.

“If we’re making things physical then multiple people can look at them and see the same thing.” / “The showing and materializing gets people to understand the idea a little bit better and see how it might be realized.”

“I think when you add the design skills there you can make it more real and believable. So what was maybe just an abstract thought expressed (e.g. in a community meeting), what designers then do is put that into form, like tomorrow’s headline on a newspaper. That then makes it more believable, and that believability helps to bring something that was just an abstract concept into something much more concrete, and that concreteness then, moving forward, other ways of thinking and decision making.”

It can also be harmful: “Designerly practices may prioritize or give too much weight to the visual, the clean, the ideal”. Funding streams may require aesthetics over other considerations that are more important in the goal of developing alternative social structures and striving for liberation.

This mindset causes us to put “artefacts first”. It can lead to an “erasure of participants”, who become “passive contributors”.

“Talking and spending time are also good methods” to build alternative social structures. Dominant Design does not allow for relationship-building without an eventual tangible output.

This prioritization of artefacts leads us to use things to represent and enable relationships, interactions and behaviors, rather than simply relating, interacting and behaving. “A lot [of the tools in the design exercise] acted as ‘containers’ in which practices would be enacted” / “We’re making things, but things don’t make societal change. There’s something missing there.”

Dominant Design focuses on technology.

“When I think about the design tools [that participants submitted in the design exercise], there were two apps and a handful of services or programs. There wasn’t a single law. What do we fall back on? What are we familiar with as designers? Maybe that means we have a familiarity with apps, we’re comfortable drawing a picture of a service. That may not be the default mode of engagement for an elected official or for an organizer.”

We know how to make “apps and tech-based platforms”, “new technological tools”.

“I think design is a good additive skill. … People who have been doing community work want to learn design because they see it as a really great additive skill for various things. For me, it’s never flipped the other way around of which design is the foundation that could address the social structures. That makes it slightly difficult when design is the premise for social change.” / As an example of design as an additive skill: “I’ve been asked to design websites, and that’s really helpful because folks didn’t know how to do it. … My mother breeds fireflies in a town in Japan, because they’ve basically died out. She’s part of a group of many other groups, one part’s cleaning the river, one’s doing education, and she’s in charge of breeding these fireflies, which is a nightmare in the house. And they have a really bad website. So nobody comes to their educational things, and I’m like ‘Let me just do this for you.’ That kind of thing. So things that we feel could be a little bit menial, like I’m not the best web designer, but I’m better than my 75-year old mother.”

“I do think that a lot of times these small [technical] interventions are quite tactical and very effective. … I’m also cognizant that some projects, especially in the space I look at, and even in the cooperative space, there can be very heavily designed intervention that actually offers something when it is around a community of that topic. I’m thinking about Loomio, which is a mediating tool for consensus decision making but it kind of– you build up a set of capacities that are more technical by using a technical tool. I don’t know if that’s good or bad, I just think that happens… There are ways that people divide roles inside worker coops if you’re trying to be horizontal– like Sociocracy is one. You really need a lot of tools if you’re trying to do it right. I don’t know, I’m on the fence about it. I’ve seen the opposite trend.”

Dominant Design is preoccupied with change, specifically with ‘innovation’ and adding new things.

“To design is to devise courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” (Herbert Simon) “That orientation towards change is both useful and problematic. I think that normative aspect, that orientation towards change is powerful. That’s part of why there’s been a turn towards design in a lot of disciplines, like engaged science and technology studies.” / Designers are “trained to explore possibilities, to see that things can change, to see connections, possibilities.”

Two things about Design’s focus on change seem problematic:

1. “Jumping to conclusions/action” and “looking for quick solutions” can make things worse than they already are. Design can be “reactive vs. thoughtful”.

2. Designers focus on “adding things over taking things away”. Design has a “preoccupation with the ‘new’”. It “values the new over the existing as a way of ignoring histories”.

Whereas an anchor institution in a community might start from an “infrastructure, or scaffold [that already exists] … the designerly approach is much more green field. It’s like ‘Let’s not even think about what’s already on the ground. Let’s start in this blank space and build everything from scratch.”

“Design thinking sometimes doesn’t take advantage of other helpful systems in place” and might “conflict with local structures”. There’s a “framing of a clean slate”. Designers often “look to create new interventions first as opposed to reconfiguring or repurposing existing ones.”

Dominant Design is extractive: it builds on the ideas of others but centers the ‘designer’.

While design ideas strive to be new and innovative, they often also appear familiar, “‘exporting’ concepts from one place to another where the culture and community might be very different”.

The concepts we developed in the exercise “were not that different from things I have already seen. They were different iterations of existing systems.”

“Is there a way for design practices to learn from people that is not extractive? What happens when something gets drawn into design practice, are there ways of doing that that are not extractive? What is the relationship of designers to people?”

Dominant Design believes itself to be neutral and objective.

Design is harmful when we “think that we are neutral”. “Neutrality is a really big script in design, I think. It goes back to the legacy again about, to be a good designer is to be able to solve any kind of problem. You get the brief from the client or commissioning party, and you’re reactive as opposed to thoughtful.”

“When you study international development, a core part of the education is critical thinking about why and how you’re doing your work. And I don’t know enough about design, but it seems to me that maybe that's missing. I see lots of it out there, the ‘decolonizing’, ‘depatriarchize’... but it’s trying to get that into the schools, and have people actually think– why do I want to be a designer? And how am I going to do it? ... For me, it’s realizing that nothing is objective. That Feminist standpoint– who you are influences what kind of things you’re going to design and bring to the table.” –Pip

Designs for alternative social structures “might not take into account complicated interpersonal dynamics.” Looking at the ideas generated in our design exercise, “a lot of these different processes have the assumption of buy-in from the community that they were existing in. They wouldn’t function unless there was complete buy-in.”

“It’s a really different set of questions if you have that investment in designing for one’s self. Those relationships can be really complicated. There are all kinds of ways that you end up embedded in community with people. And I think those things become contested. I was just thinking about a conversation I had a while ago with someone who reminded me that in the U.S. context, that when neighborhood-based organizing groups designed things (that seemed very innocuous, right?) – the Black Panther Party in the US creating the breakfast program, or creating an education program – that made them political targets as well. Because it was a political action to feed people before they went to school. Specifically to feed young black people before they went to school. So thinking about what it means to take community power in that way, and all the forms that can take.”

Dominant Design is about framing problems and systems.

“Starting with a problem” and “the creation of frames/re-framing (thinking of how Kees Dorst defines ‘design’)” made our design exercise designerly. “Analyzing structures” and “tracing/tracking infrastructures to act on them or make new ones” are also forms of framing.

“Designing has a lot of problem framing, which is both problematic and useful. ... So that way that you set that boundary around what is the site of an intervention, it could be very productive, and can redraw those in a way that opens up the way they were drawn usually. But also that closes off a lot of avenues that could be productive or it closes off avenues in ways that retrench existing inequality.”

“I always see design about making sense of some thing, creating meanings.” … “When you design something – design in terms of something with an output – you frame something. … When you frame possibilities you’re skipping other ones. In order to move forward, … you need to make a choice. In certain moments you need to be disruptive, in other ones you don’t.”

Problem framing can be harmful, for example, if designers “consider there is a problem where it is not.”

Dominant Design is structured by projects.

We think of design practices happening in time-bound ‘projects’ that can be applied to different situations.

“Designerly practices may begin to move a project or idea towards a culminating point the designer imagines, even if the community has changed its ideas or needs.” / They may “force the community into a process they would not have done by themselves.”, or “force processes that the community is not ready for.”

Designers might have “a set goal that can make people unresponsive to change throughout. When we are obsessed with that, we don’t integrate ourselves with the work of others. … It’s a process, so you’re always in the process, but if you’re in a direction, you’re not responsive. … Maybe that process has to go much slower than we want, or to stay closer to where you are [e.g. demand less change].”

At the same time, “I’m supervising a student who is doing work with regional aboriginal communities and … she thinks design’s really good at promoting and being specific about process, because design is method-centric. … she comes from being incredibly responsive to the context and who she’s working with, whereas I think she found design and, design itself defines its practice through relatively agreed terms around methods. When we say design, we can be very clear about what it refers to. We can have a pretty easy consensus around that. And that apparently is a disciplinary strength that she sees. And also by being very clear about the methods and that being used to articulate practice, she felt that would help her with her work. Partly because she’s in a role of mentoring other social workers. So... I was quite reticent about the method-centricity, its generic-ness, the double diamond four-step process, that seems quite pathetic to us, or at least to me, sorry. [But] she sees that at least as a good stepping stone into, ‘If I were to think about a framework for my practice, then how would I realize that?’ That’s been quite an eye-opener for me.”

The design-led ‘project’-based process defines relatively “short time commitments” in which to complete a certain scope of work. Since “time is needed to get involved with communities well.”, this prioritizes designers’ goals over community goals, and limits the basic activities of “talking [and] spending time”.

Dominant Design is responsible for generating ideas, separated from ongoing operations.

In a design role, we are “not responsible for the consequences” of the ideas, artefacts, programs, etc. generated through this practice. Since “intention does not equal impact”, this can end up making designers more harmful than helpful.

“If designers come up with something, develop something, give form to an idea, it’s up to these other groups of people [organizers, activists, community members, service providers, etc.] to be the ones who are doing implementation. Therefore, it’s the community members that are doing the prototype testing and who are pushing against it to see how it works and how it doesn't work” / Design can bring “hollow ambitions” to a project with a “‘start-up’ effect that they don’t see through to the end”

“Service designers are actually designing labor, they’re designing work for other folks to do. Who does that fall on? Do you have the perspective of the person that’s doing the labor or the person that’s imagining the labor?”

Looking at the ideas we generated in the design exercise, it was clear that “to get from the idea to actually making it happen, there would definitely have to be a lot more steps involved, and probably we would run into many friction points... for a lot of them it’s like, ‘This sounds great, now how do we get everyone to agree to it and participate in it?’”

People who are more embedded in community roles are “quicker to move and adjust to gaps and needs” / They might be quick to prototype solutions at a small scale in response to a need. “In Oakland, we have a couple of systems– just flyers that are like, ‘don’t call the police, call this number __’, so I think there’s people who just jump into action and create things to make solutions immediately.” “Something needs to happen, so let’s try this.”

As opposed to designers, community members “are not there on just a project basis, they have long term commitments and... if they enact a specific policy or device or app or whatever, they see the follow through and come back to it.” / “If they’re on their own territory constantly, [community members] can monitor things. [They can] be more responsive than a plan that has been made before.”

“There are case studies [on the workshop site] that feel less design-y. And the less design-y projects are the ones that look very practical to me. I can see them implemented right away without any friction. People won’t think of it as a gallery art project, but a thing that’s actually going to be used in community.”

There is an “interesting kind of dynamism, a moving back and forth represented on the community side. There are a lot of ‘ands’, like ‘this and also this’, or sets of relations. And maybe interestingly more open-endedness. I’m looking at [post-its listing the kinds of outputs that non-designers produce, like] ‘collective memory’ or ‘knowledge of community’ or ‘building on histories’, these kind of cumulative... there’s something across time.”

Workshop Proposal & Framing

Police departments across the United States and elsewhere vow to ‘protect and serve’ their publics. However, activists have pulled apart this promise to show that the system of policing is designed not to protect people and communities, but to maintain a particular organization of wealth and power. Originally created to control slaves and immigrant populations [31], the institution of policing has always served some groups while targeting others. In 2015, police killed 1,134 people. 15% of those were African American men between 15-34 years old. This group faced police-related deaths at a rate five times higher than white men of the same age [28]. Overall, contact with police carries deadly risks for racialized poor, Native people, immigrants, Black and Brown youth, LGBTQI and gender-nonconforming people, the homeless, sex workers, and others [7].

Even when people recognize these failings, and sometimes personally experience them, it can be difficult to imagine an alternative. City governments and police themselves often frame policing as the only option to address crime and prevent a descent into chaos and disorder. When people face real or imagined violence and conflict, calling the police is a concrete action to take, even when it may not result in safety or resolution. Yet activists, organizers and everyday neighbors have been enacting alternative forms of justice for generations, simply to keep themselves safe, or explicitly in order to make prisons and policing obsolete [9, 14].

This year’s conference focuses on Participation(s) Otherwise, asking us to broaden our field of vision to see these many histories, presents and futures where people believe, know and act differently from the status quo. For example, the Black Panther Party began policing the police in Oakland, California in 1966, legally bearing arms to monitor the behavior of Oakland Police officers and challenge police brutality. Later on, the Black Panthers developed free breakfast programs for school children, free health clinics, and other public services to address needs that were not being met [26]. In Chiapas, Mexico in 1994, the Zapatistas rebelled against the Mexican government to seize their own territory, where they continue to enact their own social structures, including a justice system based in community accountability [24]. Recently in the United States, an array of prefigurative initiatives enact alternatives to policing, for example the #Letusbreathe Collective occupied a vacant lot in Chicago for 41 days, vowing to address all conflict without resorting to punitive forms of justice or calling the police [21]. Creative Interventions operated temporarily in Oakland, California as a resource center to create and promote community-based responses to interpersonal and especially domestic violence, documenting their learnings in a publicly available ‘Toolkit’ [8].

As strategic and human-centered design becomes familiar in governments and nonprofits, designers are also taking on projects that address policing and the racial disparities of the criminal legal system. For example, the Los Angeles “i‑team” is one of many Innovation Teams funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies, built around human-centered design practices. They are working on improving the Los Angeles Police Department’s police recruitment and hiring process to “strengthen and diversify the police force” [6]. And New York City’s plan to replace its famously abusive Rikers Island jail with neighborhood ‘justice hubs’ was generated through a competition called “Justice in Design” [30].

Rather than strengthening the system that already exists, what would it look like for designers to embrace activists’ visions and help build alternative systems? This aligns with the political roots of Participatory Design, focused on alternative futures and democratic changes [10].

However, even when aligned with activists envisioning alternatives, it is important to question what we bring to these issues ‘as a designer’ or when acting in a ‘designerly’ way. Is it possible to contribute to relational, non-hierarchical, cooperative and dynamic systems using a practice that came with the birth of expert knowledge and modern institutions? Professional design began at a time when the determination of social norms was being lifted from regular people in their everyday lifeworlds, and instead decided “heteronomously” by designers, scientists, policy makers, and other professionals [11]. This is inherently opposed to the self-determination for which these activist groups are fighting.

Participatory designers fundamentally criticize the forms of expertise inherent in modernist design, arguing for a design practice focused in local knowledge production [4] done consensually together, and focusing on the process rather than the outcome [3]. Instead of rational problem solvers, many participatory designers strive to act as reflective practitioners, facilitating conversations-with-the-material-of-the-situation [25].

Yet participatory designers still take on and facilitate a ‘designerly’ way of working that builds from a modernist tradition, however democratized and modified it may be [3]. What does it mean to be ‘designerly’? In contrast to the focus of science on understanding how things are, design focuses on “how things ought to be”[27]. Design is based in the tangible world of experience – designers value experiential and embodied knowledge, and learn-by-doing through prototypes [15]. Ultimately, ‘designerliness’ is about working with and creating tangible things, or experiences mediated by things, to shape the way we interact with the world. This is often very different from the approach of organizers and activists, for example those listed above. They are also shaping the way we interact with the world, but often working through long-term relationship building and embodied practice.

This workshop will question the limitations of using design as a way of thinking to support the creation of these self-determined futures. Is designing systems, experiences, objects, tools and technologies a productive way to support activist visions of the future? If so, how can it be most helpful? And when could a design practice end up misleading or counterproductive instead?

*See all references here.

__

Advising and facilitation by Christine Hegel and Shana Agid

Additional facilitation by Jane Gormley

Ideation, images and discussion by Yoko Akama, Pip Bennet, Hillary Carey, Anjali Nair, Christine Hegel, Yuwei Pan, J Ryan Westphal, Luke Cantarella, Chiara Del Gaudio, Jane Gormley, Hannah Rose Fox, Dawn Walker, Shana Agid, Eleni Andris, Hannah Korsmeyer, Sandra Molina, Anja Neidhardt, and Ying Tang