January 2017 - April 2018

Futures of Public Safety

Talking and making with activists and residents of St. Louis and Ferguson, Missouri to imagine what futures without policing might look like.

In 2014, residents of Ferguson, Missouri rose up demanding justice and accountability from the city and the police officer who killed 18-year old Michael Brown. Supporters and media flooded in, and Ferguson became the site of an uprising that spread across the nation and the world. In 2015, the U.S. Department of Justice published the results of an investigation into the Ferguson municipal court and police department, exposing a range of racist practices that target and extort money from Black residents. In 2016, the city of Ferguson reluctantly entered into a consent decree with the Department of Justice, agreeing to implement a series of reforms to the policing and court systems. At the demand of protesters, this agreement included ongoing consultation with the public through an open group called the Neighborhood Policing Steering Committee (NPSC).

Futures of Public Safety worked to create a space for thinking outside of the process of police reform in Ferguson.

In official spaces like the NPSC and Department of Justice listening sessions, residents were encouraged to imagine incremental reforms that could be written into Ferguson Police Department policies. This made any form of safety achieved without police action feel irrelevant and impossible. In contrast, Futures of Public Safety worked to create space for residents to imagine futures without policing to sidestep assumptions that safety relies on police.

Futures of Public Safety worked to create a space for thinking outside of the process of police reform in Ferguson.

In official spaces like the NPSC and Department of Justice listening sessions, residents were encouraged to imagine incremental reforms that could be written into Ferguson Police Department policies. This made any form of safety achieved without police action feel irrelevant and impossible. In contrast, Futures of Public Safety worked to create space for residents to imagine futures without policing to sidestep assumptions that safety relies on police.

The Futures of Public Safety project looked like tables at block parties, creative activities at committee meetings, and exhibit/workshops in Ferguson and St. Louis. It was facilitated by Alix Gerber, alongside members of the NPSC, staff at Ferguson’s Center for Social Empowerment, and occasionally Washington University students. Early on, residents engaged in conversations about how an ideal society could respond to certain situations: driving over the speed limit, witnessing domestic violence, having a car stolen, etc. Through multiple iterations, Alix and a group of collaborators at Washington University created visuals and artifacts that built on these conversations, and then used the artifacts to spark more discussion.

In the end, three futures were developed, stretching from government-led to community-led. Each future was created as a scene of the place where police officers would have been. Instead, we see a family in their home, a social worker in an office, and a prayer team in a church. Each scene explores a dream of Ferguson residents along with its potential negative implications. The scenes and props within them do not attempt to predict or propose solutions, but rather serve as a tool for community conversations about what we want from public safety.

For residents who were working on Police Department policy with the NPSC (Neighborhood Policing Steering Committee), these conversations provided a space to discuss, for example, that safety might rely on peoples’ connection with each other and awareness of neighbor’s mental health, more than it does on police presence. Or that many Ferguson residents already work to keep each other safe through getting to know their neighbors and calling each other with any concerns, rather than calling the police. They were then able to engage with Police Department policy with this in mind, possibly pushing more towards decreasing police presence to make room for these community-led practices, rather than increasing the ‘friendly’ police encounters that are often the goal of community policing.

Community-led ︎ ︎ Government-led

Future of Grassroots Cooperation

Future of Grassroots Cooperation

Future of Hearts and Minds

Future of Public Service

Future of Public ServiceFuture of Grassroots Cooperation

The Future of Grassroots Cooperation is inspired by many peoples’ belief that community members should be responsible for their own safety. People spoke about police getting involved unnecessarily when a child breaks a window, or a dog gets loose, or someone parks in the wrong place. They talked about how police don’t help with domestic violence – what a victim really needs is friendship and support from a neighbor. In the end, community members just need to “watch out for each other”. One woman said she held the kids in her neighborhood to a strict list of rules: no sagging pants, no gambling. If a kid is acting up, neighbors ask them what’s going on. It’s ultimately about caring for each other: “If you’re hungry, you come to my house, whether you’re a kid or adult. I give them respect, they give me respect.”

At the same time, others were concerned that this would lead to more of the neighborhood violence and retribution that happens today. Without a larger structure to maintain a rational justice, it would come down to a quick emotional response. One man considered what this future would be like if a robber broke into his house: “I don’t think a thief deserves death, but in the heat of the moment, he might get shot if I’m having a bad day.”

In the imagined Future of Grassroots Participation, neighbors work together to keep their block safe. The protector scout vest (above) displays badges earned for skills like mediation and listening, neighborhood networking, education, first aid and maintenance of public space, but also the use of firearms, to ensure that neighbors can protect themselves and others against violence. The Neighborhood protectors are given bullets as a token of respect and trust, and wear them to display their responsibility. Neighbors communicate through a system of DIY radios, since a world that prioritizes community control might have more localized systems of production.

Responding to this imagined society, participants discussed the challenges that confront this vision, as well as how they would imagine it differently. We talked about how community members would need to be more familiar with each other and more willing to invest in each others’ mental health. People imagined this world as being lush and green, full of creativity and celebration of each individual personality.

Developed with Sukari Stone, Maya Mashkovich and Kristen DeMondo, based on conversations with Ferguson residents.

In a survey of Ferguson community members, people often referenced religion as a way for the community to come together, as well as a way to build a common morality. One person said that “prayer teams” should be formed to pray for those who commit crimes and do harm to the community. Another said that we don’t just need external motivation or punishment, we also need to address the “heart matter” – someone’s internal moral compass. Christian religion was often specifically called out, for example, "I would say that we should all come together as one and believe that Jesus is Lord of lords and King of kings.”

In the imagined Future of Grassroots Participation, neighbors work together to keep their block safe. The protector scout vest (above) displays badges earned for skills like mediation and listening, neighborhood networking, education, first aid and maintenance of public space, but also the use of firearms, to ensure that neighbors can protect themselves and others against violence. The Neighborhood protectors are given bullets as a token of respect and trust, and wear them to display their responsibility. Neighbors communicate through a system of DIY radios, since a world that prioritizes community control might have more localized systems of production.

Responding to this imagined society, participants discussed the challenges that confront this vision, as well as how they would imagine it differently. We talked about how community members would need to be more familiar with each other and more willing to invest in each others’ mental health. People imagined this world as being lush and green, full of creativity and celebration of each individual personality.

Developed with Sukari Stone, Maya Mashkovich and Kristen DeMondo, based on conversations with Ferguson residents.

Future of Hearts and Minds

In a survey of Ferguson community members, people often referenced religion as a way for the community to come together, as well as a way to build a common morality. One person said that “prayer teams” should be formed to pray for those who commit crimes and do harm to the community. Another said that we don’t just need external motivation or punishment, we also need to address the “heart matter” – someone’s internal moral compass. Christian religion was often specifically called out, for example, "I would say that we should all come together as one and believe that Jesus is Lord of lords and King of kings.”

In the Future of Hearts & Minds, local religious leaders ensure safety by developing the morality of community members. The prayer team stole (above) depicts intertwined wheat and tare, relating to Jesus’s Parable of the Tares. This story teaches that it is not necessary to separate wheat (good people) from the weeds (bad people) as they grow, because come harvest time, their difference will become apparent and the weeds will be burned while the wheat will be gathered in the barn of Heaven. This belief in a definite goodness and the reward of heaven might be fundamental in a society where we keep neighborhoods safe with Christian morality.

There is also an audio track of a prayer, created for this project by Barbara Kizzie (founder/host of God in the Midst radio). This prayer was imagined by Barbara to be recited with people who cause harm in the community: “Dear Lord Jesus, I believe you died for me. Forgive me of all my sin. Come into my heart, come into my life, be my lord and be my savior. Show me your ways and help me to follow them. And now I know I’m forgiven and heaven is my home. In Jesus name, amen.”

Lastly, this scene includes prayer stones that serve both as invitations to prayer that community members may give to neighbors who cause harm, as well as cues to be given to the prayer team about who to pray for.

Developed with Molly Brodsky and Christine Stavridis, prayer audio by Barbara Kizzie with Katherine Coleman.

Future of Public Service

The Future of Public Service comes from some residents’ beliefs that people who commit crimes are “coming from somewhere. It has its source, something that happened in childhood.” “Instead of asking, ‘What is wrong with you?’ [we should] ask ‘What happened to you?’ [and] help break the cycle.” Ferguson residents felt it was important to offer mentorship, jobs and employment, and suggested that people need to be taught and motivated to participate civically.

In this imagined scene, a client sits in her case manager’s office. The case manager reviews her Risk Profile, noting her risk for anti-social behavior and drug abuse. An icon indicates that this risk has been calculated due to the clients’ few living relatives, adverse childhood experiences, diagnosed trauma and drug use. This references predictive policing tools like the Chicago Police Department’s ‘Strategic Subject List’ which, until very recently, made assessments about who to target based on similar criteria. If we replace policing with an emphasis on prevention, perhaps our current preventative strategies might find their way into the picture.

There is also an audio track of a prayer, created for this project by Barbara Kizzie (founder/host of God in the Midst radio). This prayer was imagined by Barbara to be recited with people who cause harm in the community: “Dear Lord Jesus, I believe you died for me. Forgive me of all my sin. Come into my heart, come into my life, be my lord and be my savior. Show me your ways and help me to follow them. And now I know I’m forgiven and heaven is my home. In Jesus name, amen.”

Lastly, this scene includes prayer stones that serve both as invitations to prayer that community members may give to neighbors who cause harm, as well as cues to be given to the prayer team about who to pray for.

Developed with Molly Brodsky and Christine Stavridis, prayer audio by Barbara Kizzie with Katherine Coleman.

Future of Public Service

The Future of Public Service comes from some residents’ beliefs that people who commit crimes are “coming from somewhere. It has its source, something that happened in childhood.” “Instead of asking, ‘What is wrong with you?’ [we should] ask ‘What happened to you?’ [and] help break the cycle.” Ferguson residents felt it was important to offer mentorship, jobs and employment, and suggested that people need to be taught and motivated to participate civically.In this imagined scene, a client sits in her case manager’s office. The case manager reviews her Risk Profile, noting her risk for anti-social behavior and drug abuse. An icon indicates that this risk has been calculated due to the clients’ few living relatives, adverse childhood experiences, diagnosed trauma and drug use. This references predictive policing tools like the Chicago Police Department’s ‘Strategic Subject List’ which, until very recently, made assessments about who to target based on similar criteria. If we replace policing with an emphasis on prevention, perhaps our current preventative strategies might find their way into the picture.

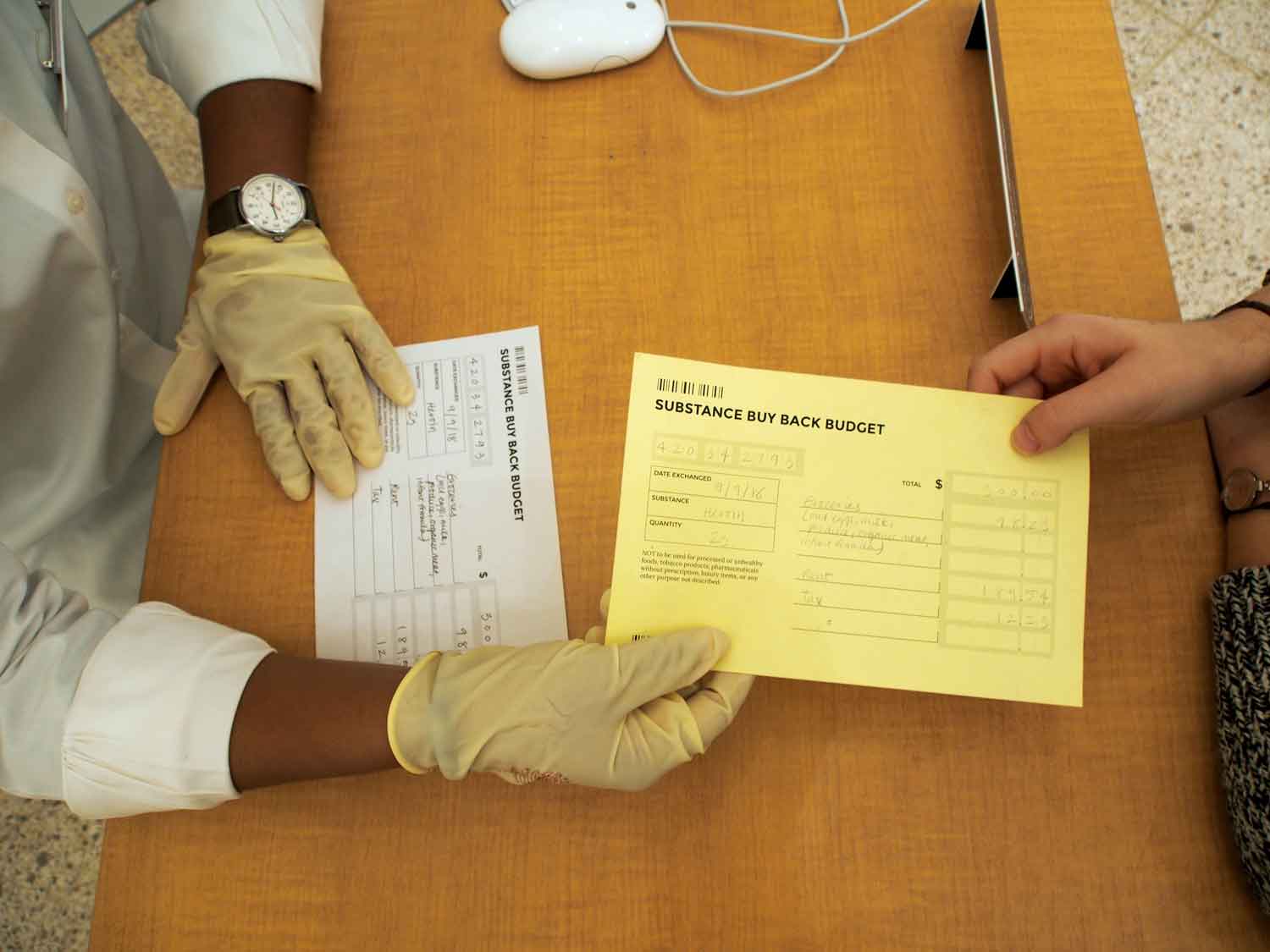

The screen also displays the client’s treatment plan and service history in a centralized dashboard of services attempting to keep each person healthy and harmless to the community around them. On the desk is a pile of Substance Buyback forms, similar to gun buyback campaigns, where people can turn in drugs for money that goes towards specific basic needs such as rent and healthy groceries.

This world replaces policing with preventative social services that strive to maintain the health of individuals in order to decrease conflict. However, it does so through a system of surveillance and control, reminiscent of current government services.

As viewers approach this scene, questions arise about how recipients of services and education would react to them. Would they have a choice about whether to take advantage of these services, or would they be forced to accept the ‘help’? And how will we determine who needs the services in the first place? How are at-risk people identified, and what does it mean to be labeled this way?

Developed with Liz Kramer.

Conclusions

While police departments imagine police officers as the sole solution to public safety, Ferguson residents imagine multiple ways to keep their neighborhoods safe in the future. This project set out to publicly recognize and broaden those different visions of public safety.

One success was in the project’s approach of visual iteration. During our initial conversations about policing in Ferguson, people struggled to visualize their abstract ideas about a world without policing. More often, they shared stories about their own experiences. Later, using the designed artifacts and scenes, we were able to have more tangible conversations about the future. People pushed against the artifacts, saying "I didn't imagine it like that." They began to describe how each future looked in their own minds. This led to greater understanding and further broadening of our shared visions, and also allowed us to have specific conversations about how different futures might address challenges differently. For example, in the Future of Grassroots Cooperation, ‘How would we need to care for each others’ acceptance and mental health in order to prevent conflict?’

However, this visual iteration can only go so far in representing the visions of residents who are not involved in the initial production of the scenes. The unfamiliar speculative design approach made it difficult to engage residents throughout the process. Despite attempts at further collaboration, much of the design work was done by Alix and collaborators from Washington University, known widely for the racial and class barriers that divide it from the surrounding community.

It was particularly difficult for us to relate to the Future of Hearts and Minds, even while this vision felt imperative to represent. Churches in the Ferguson area had played important roles in the 2014 uprising, and Christian ideals were often invoked in workshops and surveys conducted by the NPSC. We approached this future vision by referencing bible stories and church imagery, but it felt entangled with stereotypes that were difficult to navigate. One success was in getting in touch with Barbara Kizzie, host of God in the Midst radio, to record a prayer for the scene from her own perspective. In future projects, curating artifacts from experts related to shared ideals could be one way to broaden authorship.

In the end, the project was appreciated by participating activists and NPSC members for the space it provided to imagine and think beyond the confines of the official Department of Justice process.

__

Photo modeling by Maya Mashkovich, Anu Samarajiva and Sukari Stone. Workshop facilitation with John Chasnoff and Emily Davis at the Neighborhood Policing Steering Committee block party; Reybren Fitch and Nicki Reinhardt-Swierk at the Center for Social Empowerment; and Kaitlyn Schwalber at the Healthy Kids, Healthy Families Resource Fair.

Writing & Speaking

“Participatory Speculation: Futures of Public Safety”, Participatory Design Conference, Hasselt, Belgium, August 2018

“Radical Futures: Designing for Fundamental Change”, Touchpoint, the Journal of Service Design, October 2018

“Speculative Design + Designing for Justice + Design Research with Alix Gerber” [podcast] Hosted by Dawan Stanford, Design Thinking 101, June 2019

“Designing Radical Futures” [presentation & panel discussion] Dwelling in the Future: Imagining Tomorrow's City, Museum of the City of New York, New York, June 2019

“Futures of Public Safety”, Dwell in Other Futures, .ZACK, April 2018

“Participatory Speculation” [presentation & exhibition] Louis D. Beaumont lecture, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, Washington University, St. Louis, November 2017

“Futures of Public Safety” [workshop] Center for Social Empowerment, Ferguson, November 2017

“Listening & Framing: Designing Civic Experiences” [presentation] Louis D. Beaumont lecture, Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts, Washington University, St. Louis, March 2017